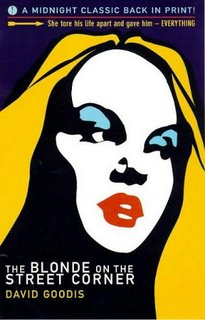

Looking to read something tortured and depressing?

If you’re looking for a good read, you could do a lot worse than this book. Particularly if you enjoy noir fiction. This novel uses the classic noir style–short sentences, snappy dialogue, terse description, a shabby milieu, and so on and so forth–at the service of a story that avoids the commonplace plots of the genre. There are no bantering private eyes here, no quick-witted cat burglars, no corrupt cops. There is, however, a femme fatale, although she’s unlikely to be mistaken for a Raymond Chandler dame Her name is Lenore and she’s the aging, insatiable wife of a piss-poor lawyer who still lives with his mother. Decidedly unbeautiful, but with certain charms nonetheless, she sets out to ensnare the novel’s “hero”, Ralph, a loser friend of her loser husband’s loser brother. To his dirt-poor family and his aimless social circle, Ralph is inoffensive almost to the point of being nonexistent, but Lenore–quicker than the rest of them–sees something more him, something that has nothing to do with love and everything to do with the rage and fear hidden underneath his mopey hopelessness.

If you’re looking for a good read, you could do a lot worse than this book. Particularly if you enjoy noir fiction. This novel uses the classic noir style–short sentences, snappy dialogue, terse description, a shabby milieu, and so on and so forth–at the service of a story that avoids the commonplace plots of the genre. There are no bantering private eyes here, no quick-witted cat burglars, no corrupt cops. There is, however, a femme fatale, although she’s unlikely to be mistaken for a Raymond Chandler dame Her name is Lenore and she’s the aging, insatiable wife of a piss-poor lawyer who still lives with his mother. Decidedly unbeautiful, but with certain charms nonetheless, she sets out to ensnare the novel’s “hero”, Ralph, a loser friend of her loser husband’s loser brother. To his dirt-poor family and his aimless social circle, Ralph is inoffensive almost to the point of being nonexistent, but Lenore–quicker than the rest of them–sees something more him, something that has nothing to do with love and everything to do with the rage and fear hidden underneath his mopey hopelessness.Hopelessness, in fact, appears to be the novel’s main theme. It is set during the depression and Goodis is unsurpassed at depicting the distinct misery of the era. Hardly anyone has a job, much less a good one, and the main characters have to scrounge to be able to afford a nickel subway fare. At one point, they treat pour salt on some celery sticks and treat it like a feast. At another, they win seasonal work in a department store stockroom and--in a perfect, heartbreaking scene that makes visceral the rapaciousness of the age–Ralph attacks his cruel boss with such violence that, for the first time, we see him as Lenore sees him. Being a victim has made him brutal, and it soon becomes clear that it’s this brutality that she lusts after.

This brings out one of the most disturbing currents in the story (and, to be fair, in noir fiction as a whole): its equation of female sexuality with corruption. The suspense largely derives from whether Ralph will submit to Lenore, whether he’ll cast aside the chaste girl he’s been ineptly wooing and his shiftless-but-true friends to give in to her rude and forbidden body. The protagonist has to decide between peace and oblivion, his better angels and his base desires. Lenore’s sexuality is depicted as all-consuming, inexhaustible, and cruel. It is, in short, a stand-in for the viciousness of society, for dehumanization and degradation.

The misogyny here is obvious. What makes this book special, however, is how it is able to transcend the typical potboiler novel gynophobia and become something else entirely. At the precise moment when Goodis could have beat us over the head with this unhappy message, he instead pulls back and shows us the sad, secret side of his devil woman. I don’t want to give it away, so I won’t tell you too much, but he leaves us with the queasy impression that kindness and violence are often indistinguishable in our cold and lacking world, a place where we fight like animals for the scraps of a life and tear each other to shreds in the name of love. This a story about hopelessness, remember, and we have to face the possibility that hope itself is the villain. In this scheme, resignation and submission might be exalted states. By showing us this, Goodis doesn’t allow his male readers the comfort of an easy, pat, sexist ending. He twists the knife in both hearts, so to speak.